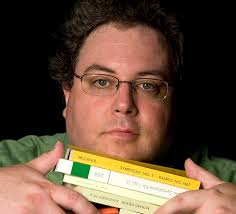

“Seven Positions” tm is delighted to bring to the fore Randy Campora: a thinking man, fully human, and exceptionally musical. From the storied bass trombone chair of the Baltimore Symphony, to a brimming infusion of brass masters past and present, to a life of varied experiences fully absorbed-Campora is focused on exceptional symphonic performances. Join him as he wanders from California to Florida on the road to Baltimore. Enjoy!

1. What childhood memories do you have of California, and Florida?

My grandparents were Italian immigrants who owned a small orchard of almonds and walnuts just east of Stockton, California. As a child I lived first on the orchard, and then in the very small town of Linden, the center of which was the high school, at which my father was the head football coach. I remember the smell of the earth when the first raindrops fell, the taste of the ripe Bing cherries, swimming in the walnut paddies flooded in the summer, the sound of the nuts being shaken from the trees at harvest, and football games in the fall.

My father changed careers when I was 11 and we moved to the polar opposite of the country—geographically and culturally—Tallahassee, Florida. It was a huge adventure for our family and we loved it. We had African American friends and classmates for the first time, acquired something of a Southern accent, experienced the food, loved the jungle-esque flora and fauna, and generally came to appreciate the wonderful people and culture of the South.

We were also blessed by the fact that Tallahassee is a college town, with Florida State and Florida A&M universities, which brought the great things of the world to the relatively small city, including great music programs, nightly orchestra broadcasts on public radio, and golf courses everywhere. I am so glad I got to live in both those unique locales as a kid.

2. What made you decide to study Spanish? And where has it taken you, both musically and non-musically.

2. What made you decide to study Spanish? And where has it taken you, both musically and non-musically.

I first studied Spanish in my last two years in high school, which served as a decent foundation for when I really had to learn it in the Missionary Training Center for Latter-day Saint (Mormon) missionaries in Provo, Utah. I was assigned to the Houston, Texas Spanish-speaking mission, and only spent eight weeks in the training center—after that it was off to Houston and sink or swim with the language.

I loved the people I met there over the next two years. They were so humble and genuine, and very patient with me as I learned their language and culture. I probably gained more from them than they did from me. Civil wars were raging in Central and South America at that time, and the people I met from those countries had sad stories to tell. Heavy stuff for a nineteen-year-old kid away from home for the first time. I also met folks from every region of Mexico, which also meant the food was excellent!

After that, I have been able to use Spanish, though not as much as I would have liked. I was in a Salsa band for a semester at FSU. Later at Peabody I taught a wonderful bass trombonist from Brazil named Joao Paulo Moreira for almost a year. We both had Spanish as our second language so we used that as our lingua franca—it worked but led to some funny situations from time to time. I would very much like to be able to make more contact with the Spanish speaking trombone world in the future, especially since they are producing so many wonderful players these days.

3. Your talent and discipline found great mentors and opportunities. What was it like to be “the kidâ€-first as a high school trombonist at FSU, and later as an undergrad in the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra?

One of the things I have marveled at as I have gotten older is the edifying attitude the more experienced players had towards me both at FSU and in the Baltimore Symphony. I was 16 when I joined the Florida State top jazz ensemble, which included many grad students. They could have turned their noses up and made life tough for a kid who was below rookie status, but they did the opposite: they taught me the ropes, expected me to come up to their level, and led by example.

I remember one night after rehearsal Jeff Thomas (now principal trombone of the Orlando Philharmonic and chief Disney trombonist) took me aside and taught me how to “blow freely†and really make a sound that could be heard inside and in front of the group. Blow Freely was the catch phrase of our professor William F. Cramer at FSU, but I had not studied with him yet, so I had to learn what that meant, to really resonate the instrument first and foremost before music can be made.

In my official Freshman year, I was invited to join the Peninsula Trombone Quartet. The other members—David Gatts, Christian Dickinson and David Burris—were grad students. They were so wonderful to work with and taught me so much, and it is to this day some of the most enjoyable playing I have ever done.

Coming into the BSO was much the same. I transferred to Peabody at the start of my third undergraduate year, and won the BSO audition towards the end of that school year when Doug Yeo won the Boston chair. I was twenty-three when I started in the orchestra, and it was David Zinman’s first official year as music director.

Eric Carlson, Jim Olin, David Fetter and David Fedderly were the icons whom I heard play each week with the BSO, and also my professors at Peabody. But they treated me as an equal colleague from the very first day in the orchestra (my first two weeks in the orchestra were Bruckner 4 and Pictures!). Eric Carlson and his wife Lorraine took me to Orioles games, and Eric was a huge influence in my education of orchestra life (what an amazing player Eric is, deserving of much greater recognition—just listen to those Philadelphia recordings with Muti and Sawallisch).

One thing I’ll always cherish is how David Fedderly, my tuba partner in the BSO for almost thirty years, approached the relationship: he never told me how to play. He just played and communicated by listening and singing out his part every single day. If I had a question I could always ask him something, but we relied on the radar method of aural musical communication. I highly recommend this approach as a way to live happily with our colleagues, and Dave was a master at it. Of course, it helps that he was one of the finest orchestral tubists in history . . .

It’s fun to welcome many wonderful younger players as new members of the BSO now. And it’s strange to now be the longest tenured member of the brass section. An orchestra really does need a mix of older and younger players—they each bring important things to the group.

4. Can you put into words the impact of Doug Yeo on your musical and personal life? His depth is considerable and his breadth is impressive.

There truly is only one Douglas Yeo in this world. I have never met another trombonist who is more committed, curious, hard-working, intelligent, self-aware, faithful and willing to serve others than Doug. He has been nothing but a blessing to me in my life, and it has been fun and helpful to keep in touch with him through his time in Boston, then at Arizona as a professor, and now as “force-to-be-reckoned-with” in the world at large. He has been an example to me in all areas of life.

I transferred to Peabody because I needed to learn how to play excerpts for orchestral auditions, but also how to play in an orchestra once I (hopefully) got a job, and I thought it was important to study with a bass trombonist. As I was deciding what school to transfer to Doug sent me a cassette of the BSO section’s presentation at a recent ITA conference. His playing, and the section’s, just floored me: so clean, balanced, in tune, colorful, solid, clear, pure and energetic.

Doug is genuinely gifted in being able to teach the excerpts in a logical, musically defensible manner, and we worked really hard that year. One of the greatest gifts he gave me was a simple one: the orchestral player is not prepared unless he knows the score, not just the piece or his part. If I had one bit of advice to give to a player in their first orchestra job, it would be that: study the same source material as your boss, the conductor, and no one will have an advantage over you. If you mark your ideas in your own score, you’ll always have those no matter what orchestra you may play in or whose parts you might use.

I attended BSO concerts at Meyerhoff Hall every week without fail, sometimes twice or three times. I was the first ever student to ask for a student discount for a full season subscription! They sent me all the tickets for the year in one large envelope. I felt like the luckiest guy on earth. To hear Doug and the section perform each week was a marvel, and it was David Zinman’s last year as Music Director Designate so that was special to hear that relationship being developed.

5. How has Peabody changed since your days as a student?

It is becoming less of a conservatory environment and more of a university setting.

When I was there in 1984-85, there was one orchestra, conducted by a seasoned professional conductor, Peter Eros, who had held posts in Malmo, Sweden and San Diego, and had been assistant to several major old school maestros. A small wind program began that same year with Gene Young working with us in small scale wind pieces like Stravinsky, Ives, Messiaen, Tomasi, Gabrielli, etc. There were no education degrees offered. There were no more than 8 total trombone students. The brass and wind faculty were almost exclusively orchestral, from the BSO and the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington. That year, the entire BSO’s trombone section was on the faculty.

Peabody gradually introduced education degrees, a jazz program, and grew a second orchestra and a wind ensemble, increased classroom requirements, and we have had up to 12-14 trombonists some years.

It seems to me that lately Peabody has lost a bit of its conservatory profile by trying to become a university music program. Heaven knows I love those programs, and FSU’s in particular, but I think it is a mistake to move away from the unique focus of a classical conservatory. Places like that don’t just grow on trees, so once you have it I think it’s best to nurture that into the future rather than expand it to the point of not knowing exactly what you are.

The other big change is that it has become so expensive that the average family cannot afford it even with a 50% scholarship. This is a problem in higher education in general, and is true of all of the non-state top music schools in the nation besides those that offer full scholarships upon acceptance. I hope we can find a way to get tuition and room/board to be more comparative to other costs families have to deal with in their lives, such as the electric bill, groceries, automobiles, gasoline, insurance, clothing, etc.

6. What are your favorite solos for bass trombone, either stand alone, or within a larger work.

Speaking frankly, if I have one professional regret it is not continuing to play recitals on a regular basis. I did for the first number of years in the orchestra, but then got out of the habit. It is such a different field of playing compared to the orchestra.

On the other hand, I also admire the great orchestral players of the past, such as Kleinhammer, Crisafulli, Jacobs, Ed Anderson and others of their generation who did not play many solo recitals—I admire the specialization and old school work ethic of digging deep to become truly great in a very specific endeavor. What a miracle it is to see great orchestral players who are such superb soloists: Charlie Vernon, Randy Hawes, Ben Van Dijk, Doug Yeo, and many others.

The solos I like to practice are also the ones I have my students work on: Spillman, Vaughn Williams, Bozza, Verhelst, Ewazen, Koetsier, Tomasi, Tcherepnin, Dossett, Hidas, Halsey Stevens, John Williams, Jacob, Marcello, Culver, Pederson, Lantier, White, Chris Brubeck, Wilder, etc.

A few lesser known solos that I think are worthy of more attention: Sonata for Bass Trombone by Carl Vollrath (published by TAP Music, commissioned by Cramer), Romantic Flash by Georges Barboteu (sort of a sequel to Bozza’s New Orleans), Tubaccanale by Boutry. I played the last three movements of Bohuslav Martinu’s Pastorales for Cello and Piano, with some edits, and really enjoyed that project, as well as Sulek’s Sonata Vox Gabrieli with a couple octave changes in the slow melodies, because my teacher, Professor Cramer, commissioned it and it’s near and dear to my heart.

We are so fortunate to have so many composers writing for our instrument now! It’s just staggering how many pieces come to us each year. I had the privilege of being Frank Gulino’s bass trombone teacher at Peabody at the time that he began composing—he’s totally self-taught—and what a major talent he has proven himself to be. Another talented student, Joseph Buono, composed a trombone ensemble piece titled Eclipse that won a contest and has been widely performed.

7. What is your secret to a great legato?

I like the term portamento to describe the embouchure action in legato: it’s the noun form of the Italian verb portare, meaning to carry. For example, if you have something valuable you want to give to someone on the other side of the room, you take it in your hands and you walk over and carry it to them—nothing jerky, sudden, or thrown around. Glissando is the more common term, but I prefer portamento.

I think of the embouchure movement from note to note as moving more slowly and deliberately, with no jerks or skips, than the movement of the slide. The slide I like to move as late and as quickly as I can get away with, though also smooth and not in a way as to mar the singing portamento happening at the lips. So the lips sing smoothly and rather slowly to the next note, while the slide waits until the last moment and goes quickly to the next position.

The slide motion I think of as business-like: it goes from point A to B at the right time relative to the lip portamento, quickly and not wasting time, smooth arm and a shock absorbing wrist, held by a precise grip of one or two finger tips and the thumb. We must always manipulate the inanimate horn in a way that it becomes a mirror for what we imagine our final product to be in our mind, and what the lips are doing as they sing like vocal chords—but in the case of legato if we moved the slide as slowly as the lips move it could come out sounding slurpy and not voice-like.

I like to think there are several different grades of legato, from my most smooth, singing, wet Bordogni style with some of the portamento showing through in the final product, to what I would call an orchestral legato which is a cleaner, more sharply defined legato better fitted to a large hall with a hundred other people on stage playing together. I can use my Bordogni legato in the orchestra if it is a certain type of solo, like Mahler’s grosse Ton, aber weich geblassen in his Seventh, which I play more like legato even though there are no slur markings. The twice repeated solo in Tchaikovsky’s “Dance of the Snowflakes” from The Nutcracker is one that I play legato and cantabile but with a somewhat more clean and clear end result, and keeps the tempo from dragging.

As is typical in America, and increasingly around the world, I use as many natural and valve slurs as I can and match the articulation to those. If forced to say what syllable I use for legato tongue, I would say a very quick Latinate “Râ€, like in Italian or Spanish, between two vowels, like in the word oro.

And as we all know, but have to work on our whole lives, the air stream for the singing phrase—be it ultra-legato or an articulated cantabile—must be unflagging and related to the phrase, not the notes in most cases, and especially not to the slide movement.

One exercise Professor Cramer used to have us do in his studio as Freshman working on Bordogni, in order to get the resonance established immediately at the first attack, was this: begin the first note of each phrase with an air attack (hOh), then use normal legato tongue in the phrase, and also do an air attack on any note inside the phrase that follows a breath. A variation was to replace the legato tongue with glissandos, along with the air attacks on the first note and following the breaths. This got the sound singing from the very first note, and got the air going immediately. It was usually done at a rather healthy dynamic level.

It is almost passe to remind ourselves to listen to great singers on recordings, from all eras of musical history available to us, but this advice is indeed crucial to develop our most profound musical goal: to sing like our mothers did to us when we were babies.

I like Domingo, Pavarotti, Jussi Bjorling, Mario Lanza, Jesse Norman, Bartolli, and a whole bunch of others. I put them on when I am playing Bordogni (those were trainers for the Rossini style after all) and try to absorb their voices like the rainwater to the ground. I also like listening to organ recordings to remind me of what a continuous air stream sounds like underneath the notes of a long phrase with many notes (organ air). I love Michael Mulcahy’s dictum: Sustain from breath to breath!

8. Can you describe the specialties of brass instruction of each of the following in a few words? What did each do best for you?

8. Can you describe the specialties of brass instruction of each of the following in a few words? What did each do best for you?

Eric Carlson: Pure sound, clean non-aggressive articulation, graded dynamics, consummate ensemble skills, superb low range, non-fussy musicality, vocal approach, sense of humor, love for baseball and ice cream, the ultimate second trombonist!

Arnold Jacobs: Eye opening lesson!, teach each person to maximize their own physical/musical potential, enhance confidence, increase consistency and predictability of musical results, freeing the mind to worry about music, how to use less muscle and more elastic air energy, articulation as speech, I see how my body works best, I played Bolero at the end of the lesson and it worked!, expert at going from an idea to a usable physical technique, the master!

Joe Alessi: Gracious (gave me a free lesson in a very busy week for him!), inspiration personified, never rests on his laurels, one of a kind, high standards, desire to serve and to give to others, super-human, expressive, healthily analytical, inquisitive, part of one of the best sections in history (Dodson, Alessi, Vernon in Philadelphia).

William F. Cramer: Model professor, man of faith, great intelligence, moral and ethical, caring, figured everything out in a vacuum out of the lime light, willing to travel the globe during the Cold War to exchange ideas and materials, encouraging, demanding, crusty but loving, true love of music, supported composers, helped birth the ITA, played Bordogni accompaniments on piano in lessons, no nonsense, didn’t fix what wasn’t broken, fearless, blow freely!

9. As a young bass trombonist in the 80’s, how much did Charles Vernon influence you? How do you view his contributions to the instrument?

I first heard Charlie’s playing via two mono cassette recordings that Dr. Cramer loaned me that he had made himself at the ITA workshops in the mid to late 70s. I was just transfixed, utterly stunned at the musical presentation, the sound, range, control, singing vibrato, the whole thing just floored me. It just seemed like he was playing bass trombone like the angels intended!

I first got to hear him live when FSU went up to the Eastern Trombone Workshop held at Towson State University in Baltimore in 1979 or 1980. He played the Vaughn Williams Concerto and the Bozza Quartet. I can still hear every note of those tapes and those performances, I still know where he breathed and how he phrased.

As the years went on, I heard him several times live with the Philadelphia Orchestra, played trombone ensembles with him and my BSO colleagues in his basement, wore out many CDs and LPs of him with Philadelphia and Chicago (and early Baltimore Symphony recordings—check out his Nutcracker on YouTube or iTunes with Comissiona conducting), and had a couple of lessons with him.

Charlie has done so much for our instrument, I hope he realizes this in his moments of wondering self-doubt, if he ever has them, because his contribution and example are so magnificent. He personifies what Jacobs and Kleinhammer taught, and to be able to hear that buoyancy in the sound and approach is priceless.

The Baltimore Symphony, minus myself, has got to have the greatest bass trombone pedigree of modern history: Ted Griffith (went to Montreal), Charlie Vernon, John Engelkes, and Douglas Yeo. I cannot imagine a better set of players to have to attempt to live up to. I have tried to incorporate a little of each of these players in my orchestral approach (a big shout out to John Engelkes, whose playing I adore).

It’s hard to not hear Charlie’s example in one’s mind whenever one is playing a major orchestral piece that he has recorded. That can be a burden–a siren song to maybe tempt one to reach a little past one’s own self in terms of volume or presence–but if kept in perspective it is a huge guiding star. If I could say one thing to Charlie it would be: thank you! And if I could say one thing to Gene Pokorny it would be: you deserve a medal!

10. What human experiences and emotions have informed and enriched your music-making as you travel through life. How has the tapestry of life become fuller in a way that has infused your music.

There is so much one could say in answer to this, but I’d like to respond with things I have learned as part of an ensemble and organization for over thirty years.

I have learned that over the years, as important as the music is, as important as your professionalism is, as your attention to your playing is, that people are more important. Take your relationships with your long-term colleagues seriously, thoughtfully, and when those relationships are working well try to enjoy them, because there is no law that says it will always be that way.

In what other profession can you work with the same colleagues on your left and your right, sitting at a distance of 18 inches on either side, for several decades at a time, working as a team in a non-verbal setting, with your boss looking at you every single minute you are on the clock, dressed in white tie and tail coat, holding five pounds of metal, with the express purpose of giving hope, entertainment, faith, inspiration, enlightenment, and art to two thousand people at a time?

Show your respect and love for your colleagues, especially the ones in your own section: always be prepared (musically, mentally and physically); be willing to self-diagnose problems in your playing and work until they are solved, so you and your buddies can all be happy; listen as much as possible, give the benefit of the doubt; give yourself slack in those moments that you are the weak link.

Stay on the section bus and don’t drive away on your own bus; express openly your respect, admiration and love to each other; don’t diagnose the problems of others; make your most important statements through your playing and actions, not with your words; cultivate self-awareness; share your best ideas and experiences with your colleagues; be positive in your own way (yes, you can be cynical and positive if that is your personality).

Foster an atmosphere worthy of the greatness of the music; respect the stage and all it represents, at all times; put the cell phone away and open the score, pay attention to rehearsal; don’t wait too long to express important things to colleagues who are important to you, in an appropriate way, because the chance might be gone forever.

I have also had significant experiences working on non-musical areas of the orchestra, as chairman of orchestra players’ committees, orchestra artistic planning committees, feedback groups for young conductors, music director search committees, fundraising groups, and audition committees.

These tasks can lead to some painful moments of frustration, even failure, but as I look back I see that I met some wonderful people that I otherwise would have missed, and I developed skills that in some cases I didn’t know I even had. Are there things you can do in your organization that will give service and also help you develop yourself more?

I was once offered a spot in a downtown law firm, if I ever got a law degree, by the head partner after I gave a speech to the board of directors. I got to know bank presidents, owners of major league sports teams, leading bio researchers, mayors and governors. It is also a good way for your own managers and executive directors to get to know you and your value to the organization.

But there comes a time when you also have to say Basta! and focus on your practice and leave some of that stuff behind.

Probably my favorite moment where life and music intersected was the day our second son, Rafael, was born.

He arrived in the wee hours of the morning on a weekend. My wife was feeling fine, Raffi was healthy, my mother-in-law was taking care of our oldest son, Dominik, and my wife looked up at me in the morning in the hospital and said: “You know, I really think you should play the concert tonight and celebrate Raffi’s birth that way.†I asked her ten times if she was really sure, and she confirmed it each time.

That night was David Zinman’s last concert of his tenure as music director, and the piece was Bruckner’s 8th, perhaps the most transcendent work in the literature. It was such a joyful experience—I was floating on a cloud the whole time and every note came out a gem. It taught me that we can use our life experiences in personal ways to make performing a joy for ourselves and our audiences.

11. What do you look for in a bass trombone? How has it changed?

I look for an openness that can also be controlled in all registers and dynamics, a good relationship between inner focus and outer radiance (bloom), ability to project with warmth and color, clarity of articulation, ability to meld into the other players but also step forward towards the audience when needed. It also must ergonomically fit my body comfortably.

I don’t like horns that tempt me to push too much with the abdominals (heavy horns do that to me). I like horns that help me focus the higher I go, and help the sound blossom the lower I go, and have predictable mid-range response (for all those soft sustained notes in orchestral parts).

Right now I use an Edwards dependent axial valve section, a 1575cf bell (22 gauge yellow brass, soldered rim, heat treated, cf treated, 10†diameter), a yellow brass single radius tuning slide, a 502-V single bore slide (rose tubes, yellow crook, #2 brass pipe), and a Griego .5 NY mouthpiece. I also have the rose brass version of the bell, a 1574cf, which I can use for earlier composers—it gives a slightly more classic German profile.

My theory as to why I like the 10†bells is that the extra quarter inch all around adds a bit of weight without a thicker wall, and is not larger enough to cause any negative acoustical patterns. Perhaps similar to a German kranz but not overlaid on the bell.

I just recently switched to the single bore slide from the dual bore after many years. The new 502 design seems to give me the best qualities of both, but with easier control, more color and easier projection. The dual bore skews more towards the contrabass profile, which is great for many things, but not perfect for all things.

We have so many wonderful trombone makers on the planet now, it’s astonishing!

In the past I used Bachs for many years, with Schilke 60 mouthpieces of various rim sizes, backbores and shanks; Minick L or OL pipes; Thayer valves, mostly dependent setups, but for a while an in-line (in-line Thayers don’t fit my neck/jaw very well and mess up my ability to get the mouthpiece in the right spot on my face).

I don’t own a contra, and neither does the orchestra. We don’t play the opera literature often enough, or orchestral contra pieces, to justify it for me. I have played contra on a few occasions when I could easily get my hands on a loaner. When we play Wagner Ring excerpts I use my normal horn and try to transform into a contra sound and approach, a la Steve Norrell (go Steve!).

c. David William Brubeck All Rights Reserved. www.davidbrubeck.com

Photos courtesy of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and The Peabody Conservatory

Interested in more “Seven Positions†tm Interviews?

Charlie Vernon

James Markey

Chris Brubeck

Doug Yeo

Jeremy Morrow

Tom Everett

Gerry Pagano

Ben van Dijk

Randall Hawes

Denson Paul Pollard

Thomas Matta

Fred Sturm

Bill Reichenbach

Massimo Pirone

Erik Van Lier

Jennifer Wharton

Matyas Veer

Stefan Schulz