Bubert, Kagarice, Norrell and Sulliman-“The Fourth Valve” in 2016 had all its basses covered! A large percentage of the content of the Journal of the International trombone Association (ITA), is left to Dennis Bubert’s care each quarter as he places the major symphonic works and players of our time in the spotlight. Bubert represents pedagogy, ability, accomplishment, scholarship and a front row seat to the ride. Jan Kagarice has made a specialty out of helping those who had been injured or needed to overcome some form of limitation. No stranger to medical issues, Jan had resolve them to continue to play trombone and it became part of her character. In the same way, performing as the bass trombonist of the successful PRISMA trombone quartet helped her to coach a number of award winning trombone quartets from UNT. A true Metropolitan Opera bass, trombonist Steve Norrell has been a stalwart in the Met Orchestra, proving his longevity and passion for music. Trained at Juilliard and by members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, he has grown to embody his own musical voice and perspectives. An American original, he has recently returned to the recital stage with a world premiere of a sonata dedicated to his mentor, CSO bass trombonist Ed Kleinhammer. Jason Sulliman is a bass trombonist with a passion and a purpose. Originally a cast member for BLAST!, Sulliman is now its conductor and manager, and has sought to integrate his personal experiences as a performer with his passion for helping others through education. Along the way, kinesiology just sort of “happened”, and has become a growing area of fascination and expertise.

Bubert, Kagarice, Norrell and Sulliman-“The Fourth Valve” in 2016 had all its basses covered! A large percentage of the content of the Journal of the International trombone Association (ITA), is left to Dennis Bubert’s care each quarter as he places the major symphonic works and players of our time in the spotlight. Bubert represents pedagogy, ability, accomplishment, scholarship and a front row seat to the ride. Jan Kagarice has made a specialty out of helping those who had been injured or needed to overcome some form of limitation. No stranger to medical issues, Jan had resolve them to continue to play trombone and it became part of her character. In the same way, performing as the bass trombonist of the successful PRISMA trombone quartet helped her to coach a number of award winning trombone quartets from UNT. A true Metropolitan Opera bass, trombonist Steve Norrell has been a stalwart in the Met Orchestra, proving his longevity and passion for music. Trained at Juilliard and by members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, he has grown to embody his own musical voice and perspectives. An American original, he has recently returned to the recital stage with a world premiere of a sonata dedicated to his mentor, CSO bass trombonist Ed Kleinhammer. Jason Sulliman is a bass trombonist with a passion and a purpose. Originally a cast member for BLAST!, Sulliman is now its conductor and manager, and has sought to integrate his personal experiences as a performer with his passion for helping others through education. Along the way, kinesiology just sort of “happened”, and has become a growing area of fascination and expertise.

DENNIS BUBERT

6. How have your views on Kleinhammer’s pedagogy changed from 30 years ago? (Can you imagine a brass section where he , Jacobs and Farkas were writing their books and conversing?)

6. How have your views on Kleinhammer’s pedagogy changed from 30 years ago? (Can you imagine a brass section where he , Jacobs and Farkas were writing their books and conversing?)

Both were very involved with what I consider one of the most predominant themes in brass pedagogy over the past three-quarters of the century, but in their own unique way. You’ve no doubt heard the state of trombone playing Emory Remington encountered early in his career, and how his teaching style evolved to urge students to adapt a more singing approach to the horn, blowing into it with as little resistance as possible. This idea of a more relaxed, easy way of blowing the horn was also a major theme in the teaching of both Mr. Kleinhammer and Mr. Jacobs. For Jake, that was reflected in the admonition to “play with minimal motors†and “to seek the weakness in your playing.†Ed, who was quite taken with the Eugen Herrigel book, “Zen in the Art of Archeryâ€, co-opted Herrigel’s expression of “effortless effortâ€. He carried that book around in his jacket pocket from one time to another, and I remember the countless times he bolted across the room to grab it from his coat and read a paragraph. He also talked about “blowing the horn in a spiritual way.â€

I was incredibly, incredibly fortunate to be able to study with those guys, and I’ve often marveled at whatever set of happy circumstances brought them all together at that time in that one place. I don’t think I ever had a lesson with either of them without them invoking the name of Adolph Herseth, and over the years I’ve come to think of them thusly: Herseth as the ultimate artist, Jacobs as the ultimate scholar, and Ed as the ultimate student. Tim Smith told me that a couple of his friends saw Ed at the old Schilke shop on South Wabash once, and screwed up their courage to go over and introduce themselves. “Mr. Kleinhammer? Hi, I wanted to say hello…I’m a trombone studentâ€, Tim’s friend said. “You are?â€, Ed exclaimed…. “I AM, TOO!â€

I have photos of Ed and Jake in my studio at school as well as on the wall of my basement practice area at home, and I can honestly say that not a single day has passed without thinking about my time with them. Truly extraordinary individuals, and the giants of our art on whose shoulders we stand. I told Charlie last week that I can’t walk down Michigan Avenue or be in the basement of Orchestra Hall without sensing their presence.

8. Red herrings are a literary device used by mystery writers to throw readers off the track. Do you see any red herrings or unfruitful pursuits in the advancement of the bass trombone at the moment?

Red herrings? I don’t know about that, but there is one unfruitful pursuit, as you put it, that I frequently encounter in students. And that’s students who are so enamored of some of our more prominent trombone personalities, like Joe and Charlie, that they’re obsessed with trying to emulate them. Those two are marvelous trombonists and musicians, but as wonderful as they are, I think it’s important for us as musicians and instrumentalists to find our own voice. It’s hard enough to be yourself without trying to be someone you’re not.

To read the rest of the interview, click here: Dennis Bubert

JAN KAGARICE

2. What were your teaching style and objectives like before you had medical challenges as compared with afterwards?

2. What were your teaching style and objectives like before you had medical challenges as compared with afterwards?

I have a form of muscular dystrophy and a rare neurological disorder. Neither of which are life threatening but certainly caused me to learn about efficiency and healthy function.

My objectives in guiding musicians has ALWAYS been about the music. I believe that the music itself is the teacher. My students call me coach… I’m just coaching their focus of attention to the music, pretty easy gig! 😉 When a player has physical issues that interfere with performance, I assist them is becoming more efficient…. doing LESS. That’s why they are called “LESSons†😉

“Janet”, Performed by Maniacal Four Trombone Quartet in dedication to Jan

6. It has been said that people “play their personality”. How much of a compelling factor for a performer is the character, humanity and temperment that infuses the performer?

I agree with the statement completely, but it is also important for the performer to not let their personality overshadow the expression of the composer brought to life.

Follow aong with the rest of the interview here: Jan Kagarice

-

2. What is your secret to a good legato?

My concept of legato is having the continuity of wind, an efficient embouchure and a fast and elastic slide arm. Many players work so hard trying to have a fast slide arm, but their wrist is rigid and they can only move their slide as fast as they move their whole arm. Obviously this is not smooth and is awkward to listen to. John Swallow’s trick was to put a tight rubber band around your outer slide which is parallel with the brace between the upper and lower slide. This is the same area where you normally hold your slide, but since your fingers are wedged between the brace and the rubber band, you can take your thumb off the slide which frees up your wrist. Adding this elasticity to your wrist is essential for legato and any relaxed fast slide movement.

John Swallow liked students to change partials if they did an interval larger than a 3rd. It’s a good rule to experiment with, but I believe the other part of the equation is the embouchure being efficient. In my early Met years, Pavarotti would go from one interval to the next immediately, without bumping the new frequency. I believe it’s the same on our instrument. There’s a fine line between having a good liquid legato, but not being stiff or rigid. Jay Friedman frequently tells students to play a “slow slur,” which is what I interpret as Jay trying to get the student to blow through the legato. I’ll often ask the student to have a quicker and more efficient embouchure without bumping the notes. I think that Jay and I are approaching the same thing from different sides of the equation. I encourage students to buzz legato phrases only using their tongue on the initial attack after a breath. After that, the clarity should come from the efficiency of the embouchure. It has to be trained! Even with students who prefer to use legato tongue, I encourage them to buzz the mouthpiece only using the tongue on the initial attack. If their embouchure becomes more efficient, whatever amount of legato tongue they were using inevitably becomes less.

The stimulus that I use when I play legato is thinking that it’s smooth. Personally I try to have the tongue out of the way as much as possible, but when I’m playing, being smooth is primary and anything else that I’m doing to achieve this is a trained reaction and secondary.

My two favorite legatos that I’ve personally encountered are Charlie Vernon’s and Norman Bolter’s. It’s not a coincidence that Jay Friedman studied with Swallow before he got into the CSO or that Norman studied with Swallow in school or that Charlie commuted to NYC while in Baltimore to study with Swallow.

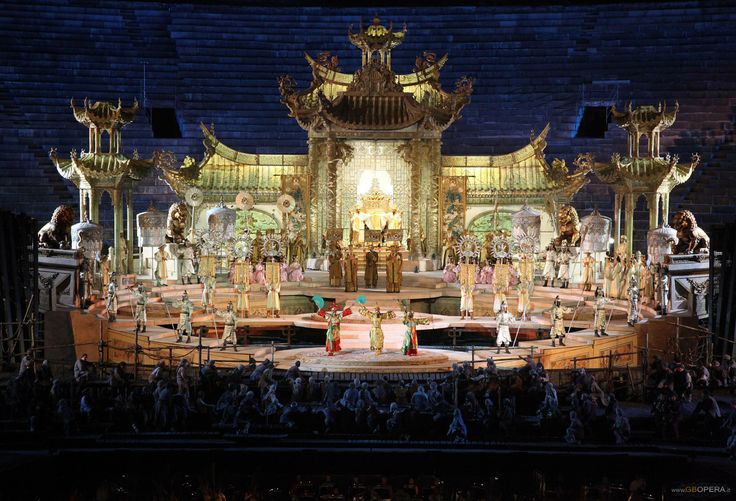

(After performing the New York premiere of the Edward Kleinhammer Sonata in recital at the Manhattan School of Music in November of 2015 with pianist Hanako Yamagata, bass trombone virtuoso Steve Norrell was invited to encore the sonata at the 2016 Festival of the International Trombone Association. The Norrell/Yamagata collaboration is planned to be held at Juilliard, on Friday the tenth of June, 2016, as part of the international festival’s emphasis on trombone solo artists.

The new sonata, which was written by composer John Stevens, is dedicated to one of the finest orchestral bass trombonists and brass pedagogues of the past hundred years-Edward Kleinhammer. Published by Potenza Music, the Stevens composition combines an intimate knowledge of the capabilities of the bass trombone (which the eponymous Kleinhammer did so much to define), along with expressive lyrical settings, a wide range of timbrel colors, and distinctly virtuosic passages combined with a hypnotic piano accompaniment.)

CLick here to watch and listen to the premiere…

8. How would you contrast the “New York School” of trombone playing of Joe Alessi with what you learned in Chicago?

Joe Alessi is such a unique person. He is one of the hardest working individuals I’ve ever known! The progress that he’s made since he became principal trombone of the Philharmonic is monumental and he’s always looking for ways to incorporate new things into what he does. During Joe’s early years, we had a weekly racquetball game and would occasionally play together. Simply tremendous! Since those years, certain aspects of his playing have improved exponentially. Playing a job like the Met, I was always envious of the freedom and flexibility that Joe had in doing outside projects. Of course I’m happy for Joe and it’s hard to imagine anyone being more productive while they were doing it.

Joe is a little younger than I am, but he was at Curtis while I was at Juilliard and all of us of that era were positively affected by the CSO. Joe’s greatest influences were his father, teachers in the Bay Area (Ned Meredith and Mark Lawrence) and then Dee Stewart and especially Glenn Dodson at Curtis. Many years ago I had conversations with Joe about my lessons with Mr. Jacobs. He was interested, but his concepts are uniquely his own on certain things. He’s been very successful in developing so many amazing artists, In 1988, the CSO was doing a residency at Carnegie and their off day that week was on Thursday. Charlie and Jay came up to the house in the afternoon as did Joe and David Finlayson. We played for hours (while I had the tape recorder on). Listening to the tape I hear individuals. It’s all really, really good, but unique to the person who was playing it. Since that time, Joe’s playing has only grown!

Follow your favorite operatic bass here: Steve Norrell

JASON SULLIMAN

2. If movements are like fingerprints, and each is different everytime; can there be any constants in trombone technique?

This is a difficult question to answer in that the product and the process to get there have different spins on the same answer, and to many this will sound like an academic quibble of semantics, but I disagree. I find the whole concept fascinating.

Technically I don’t think any two sounds made in the natural world are identical. Movements are all different (even if it is so slight that it is unperceivable to the human ear) and thus their fingerprints in sound are unique. Musicians will usually get to a point where for all practical purposes, a consistent sound is heard because the nuances are so minute that they aren’t significant in terms of job performance, etc. For that part of the conversation, I do think one can approach playing with a consistent mindset and achieve consistent results, but only if we use the terms loosely. I don’t think there’s any real harm in talking about a consistent product as long as we agree it is a matter of scaling.

I think the word ‘consistent’ can be dangerous though, when talking about the process. If we get so wrapped up in trying to manipulate our bodies the same exact way every time, we might actually be hindering our bodies’ natural ability to adapt to the current environmental parameters and take aim at that ‘consistent’ goal from a slightly different vantage point. Your body’s components must function from their current state, and to interfere with our natural ability to function might limit the freedom of adaptability. The only ‘consistent’ thing about my playing is I am constantly trying to be better than yesterday. I think the whole concept of ‘consistent’ sets limitations and throws our focus off of the real goal.

7. How do your studies movement influence your approach to slide motion?

My slide movement needs a ton of work, mainly because I am still searching for the best set-up in the left hand to hold the horn. I think this matters with bass in particular. It is a heavier horn, and if your left hand doesn’t feel comfortable supporting the instrument for long periods of time, then it will start shifting in a way that eases the discomfort. When that happens the right hand will naturally make compensating adjustments with how it helps to support the weight of the instrument, which will change the slide technique.

Having said that, I try to hold the slide with my fingertips. After that, I really try to ignore the physical characteristics and focus solely on the sound that is created when changing notes. If you are really listening, you can hear a difference between effective slide technique and ineffective slide technique on all sorts of levels. This goes back to ‘no two movements are alike’. I challenge you to find two trombonists that do it the same exact way. I guarantee if we hook them up to measurement equipment (like EEG), we will find differences.

I remember watching the National Brass Ensemble concert in Chicago last year. Some of the Gabrieli pieces were set up with two choirs, so their angles were such that I got a great look at slide work. There were times where I saw some of the most accomplished trombonists playing unison lines right next to each other. Slightly different hand positions, different speeds, but wonderful results. I could only tell a difference visually.

To keep relaxing with Jason, click here: Jason Sulliman

c. 2017 David William Brubeck All Rights Reserved www.davidbrubeck.com

Interested in more “Seven Positions†tm Interviews?

Charlie VernonJames MarkeyChris BrubeckDoug YeoJeremy MorrowTom EverettGerry Pagano Ben van DijkRandall HawesDenson Paul PollardThomas MattaFred Sturm Bill ReichenbachMassimo Pirone Erik Van Lier Jennifer WhartonMatyas VeerStefan Schulz